How to grow muscles: Introduction to Nutritional Biochemistry, Part 2

After looking at the science behind how to shrink fat cells in the previous post of this 5-part series, we now turn our attention to muscles and how to increase their size.

As you might expect, the biochemistry behind this process is extremely complex. My goal here is to introduce the basic science while attempting to cover enough of the essential components so you can (1) avoid getting fooled by all the pseudoscience out there trying to sell you something, and (2) have practical takeaways for your own workouts.

Summary

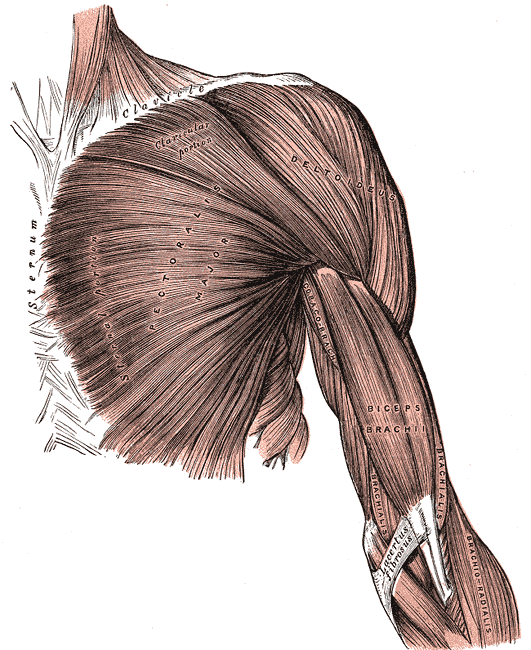

Lifting heavy things results in micro-tears within muscle fibers. These tears invoke an inflammation response and activate various stem cells that fuse into to the broken fibers to increase mass to help prevent tears in the future when lifting similarly heavy things (hence why you need to keep increasing weights and workout different parts of a muscle — with different contraction types and tempos — for maximum gains).

Not surprisingly, the muscle fiber types that are designed to help us lift very heavy things (i.e. fast twitch, IIX) are the ones that break most often while lifting weights and thus contribute most to bulking up. This happens after a month or so of your body first getting stronger by optimizing nerve firing, blood flow, and energy utilization.

To gain muscle mass, look for professional trainers and lifting programs that focus on Type IIX fibers and a large degree of lift diversity and rest. The name of the game is mechanical tension, muscle damage, and metabolic stress, which I’ll talk more about below.

To lose muscle mass, just keep hitting your easy-to-moderate walking/jogging/treadmill/elliptical/bike without lifting weights (as only your smaller Type I muscle fibers will be activated).

As you might expect, muscle gains are hormonally and genetically controlled. They are, however, extremely related to sleep, hydration, flexibility, and especially diet.

Ready to learn about the details?