A primer on viruses, antigens, antibodies, contagiousness, vaccines, and COVID-19 testing

Like millions of households around the world right now, my family and I recently caught a virus. Trillions of the little buggers invaded at least my sons (9 & 14 years old) while my wife and I - along with our 12-yr old daughter - wondered if we were all getting COVID-19.

This is, of course, a common scenario. Our tests came back negative, but during the 70 hours we waited for results, we spent a lot of time researching immunology and discussing what to do. We felt generally unprepared and uneducated about how to think and act clearly.

This article is designed to help inform us how to think and act in such a scenario by better understanding the underlying science. I spent the better part of a decade in a bioengineering lab (earning my PhD at ETH Zurich in 2007) and it was - and still is (!) - rather difficult for me to make sense of what’s out there. It is critical that all of us know how to collectively approach the upcoming vaccines, rapid antibody tests, rapid antigen tests, and PCR tests (do you know the difference?). We need to understand the underlying science in order to combat fake news, conspiracy theories, unhelpful economic forces, and good old-fashioned politics that are preventing us from quickly fighting this disease.

I agree with Michael Mina, MD, PhD (Assistant Professor of Epidemiology and Immunology, Harvard) that if we were all equipped with rapid antigen tests, we could defeat COVID-19 within a month. Check out this article he wrote in Time and this podcast he did recently with Lex Fridman.

I’ll explain below why I agree with him and many others in the scientific community. In order to truly understand the argument, however, it first requires a primer on viruses, antigens, and contagiousness, which I’ll begin with below. We’ll then finish by talking about antibodies, vaccines, and COVID-19 tests.

What are viruses?

There are over 200 types of viruses that cause the symptoms of a common cold. Over half of such illnesses are caused by rhinoviruses, and the rest are to be blamed on coronaviruses, RSV, and parainfluenza.

Here is a fantastic graphic from Harvard Museums of Science and Culture explaining the four types of virus vehicles:

And - to go a lever deeper - there are seven classification of viruses (known as the Baltimore Classification), which can be reduced to either RNA or DNA types and host-domain types. Here is great graphic showing those classifications (“ds” = “double-stranded” and “ss” = “single-stranded”):

Long story short, there are tons of viruses out there. Our own bodies, in fact, have trillions of viruses called bacteriophages that compose our virome.

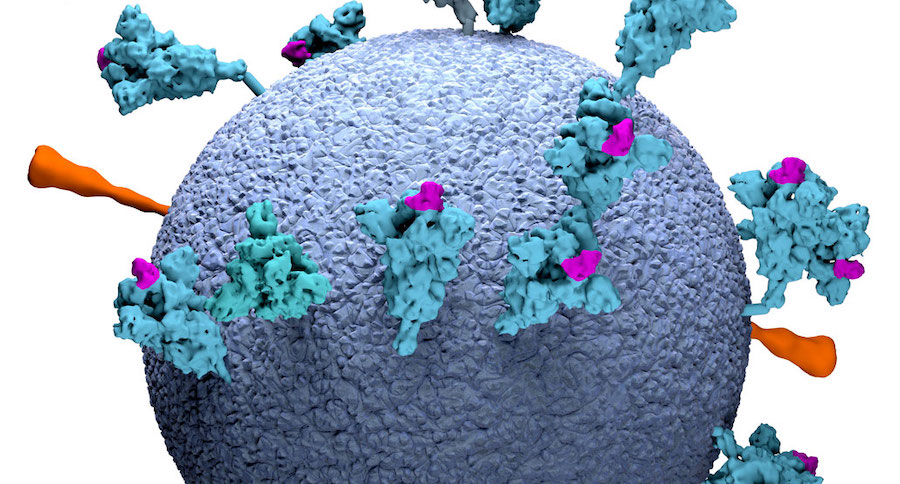

For our purposes here, however, we are concerned with SARS-CoV-2:

What are antigens?

In the graphic above, those spike proteins are called antigens. An antigen is anything (usually a molecule like a protein) that can be bound by an antibody and cause an immune response. For the purposes of a quick primer here, that’s pretty much all we need to know about antigens. The various antigen tests out there for SARS-Cov-2 usually detect those spike proteins, and the “rapid” tests are similar to pregnancy tests; with a simple nose swab they can tell us in a few minutes if we are shedding SARS-Cov-2 and contagious. This is a big deal.

Contagiousness: The Common Cold vs. Flu vs. COVID-19

In order to understand what all the fuss is about rapid antigen tests vs. the more common reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and other nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), it’s first helpful to understand how contagiousness works. If we all knew when we were actively shedding SARS-CoV-2 (i.e. contagious) then we would know when to stay away from people.

What makes COVID-19 hard to beat, however, is that people can be extremely contagious without symptoms. This is either because they are pre-symptomatic, or it’s because they will show little or no signs of symptoms whatsoever while infected and actively shedding virus.

First, here is a quick look at the incubation period and basic symptom onset profile of COVID-19 vs. Flu vs. the common cold:

This is what makes COVID-19 relatively tricky to beat and why people have a hard time understanding the differences between COVID-19, the flu, and common colds. If COVID-19 was incubated quickly, then the global pandemic never would have happened (similar to how SARS, MERS, Ebola, etc... were contained relatively quickly).

However, here is a quick graphic from the NY Times showing the issue with COVID-19:

In other words, with a cold or flu, the time between exposure and symptoms is much shorter, so the viral loads correspond roughly with symptoms. This is what people are used to. It’s also why people are running around spreading it unconsciously.

To put it another way, here’s another simple graphic from MIT regarding COVID-19:

So, with this background, now we can understand why rapid antigen tests would be so helpful. We could identify the highest viral shedding zone for ourselves (red), even if we had no symptoms:

While of course the PCR tests are dramatically more sensitive, if everyone could do a quick test on themselves a couple times a week, we would beat COVID-19 within a handful of weeks.

What are antibodies?

Antibodies are what our bodies create when they detect antigens. Here is a fantastic overview of how our immune system works, and here is a great video explainer.

In short, we have many different types of antibodies in our immune system to help us fight diseases, but what you will commonly hear with regard to antibody testing for COVID-19 is IgM and IgG. Here is a helpful graphic showing when a healthy immune system fires up IgM and IgG in response to COVID-19:

The way that rapid antibody tests work is to put a drop of blood on a simple pad like this which will detect COVID-19 IgG and IgM:

How do these new COVID-19 vaccines work?

With the above background, explaining the new vaccines is relatively simple. In short, the new vaccines from Pfizer/BioNtech and Moderna inject mRNA into our bodies to produce antigens (the spike proteins) that our bodies then create antibodies against.

That’s it.

While the underlying technology is amazing, the basic concept isn’t hard to explain and shouldn’t be too scary, especially now that clinical trial data has shown the effectiveness is super high (95%+!) and side effects super low. About 10% of people after the second shot will experience flu symptoms, but they will go away in a few days and are signs that the vaccine is working.

For a fantastic in-depth explanation about how these new vaccines work, I’ll refer you over to this interactive NY Times piece.

Why don’t we all have rapid antigen tests freely available in our homes?

Good question. As I linked to above, Michael Mina, MD, PhD (Assistant Professor of Epidemiology and Immunology, Harvard) is helping to lead the charge in the USA. Again, I’d highly recommend this podcast he did recently with Lex Fridman.

In that podcast, Dr. Mina explains that there are complex political and economic forces at play (at least in the USA), including a vague jurisdiction issue between the FDA, the CDC, and the White House.

He has spun up a website (https://www.rapidtests.org/) which has a lot more information, but here is a helpful graphic on that site about the types of tests to detect the presence of active virus:

Per his website, I will echo the calls to action:

- “Text RAPID TESTS to 50409 to send our latest (December 2020) letter to your senators and representative. Please send this new letter even if you previously sent an earlier letter! Or if you prefer email, you can view the letter here and then email it to your representatives (links provided).

- Once you have sent a letter, please share this website with others, and encourage them to do the same.

- Join our Facebook group or subscribe for more updates, below.

- For even more ways you can help, see the last question of our FAQ.”

Conclusion

Filling in details from the story I shared at the opening of this article, at the onset of symptoms recently, my family and I wore masks, got tested, practiced social distancing in our own house, washed our hands and surfaces frequently, made sure to separate towels used in bathrooms, and followed as many of the other recommended guidelines from the CDC as possible.

Until rapid antigen tests for COVID-19 are widely available, we all essentially have to assume we have the disease unless we’ve recently had a negative test and haven’t been around other people. Antibody tests can, of course, be useful to detect how effective our vaccines are and whether or not we’ve been infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the past. Still, even with positive results for IgM/IgG antibodies in our blood, the science behind how effective these antibodies are for the long-haul have yet to be determined.

Author’s note: thanks in advance for any/all questions and comments on the above article. Feel free to email me directly at will@wclittle.com or hit me up on social media (I’m @wclittle in most places). Feel free to subscribe to my newsletter, where I write occasionally about health science, startups, software development, and things I’m discussing with my podcast guests. Thanks!